IPBES Report: Biodiversity Loss Is a Business Risk

In February, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) approved its Business and Biodiversity...

4 min read

Sebastian Leape

:

Updated on February 24, 2026

Sebastian Leape

:

Updated on February 24, 2026

Over the past year, I’ve noticed a striking shift in the public conversation about nature. Protecting habitats and species is increasingly framed as the main barrier to economic growth. Here in the UK, politicians have obsessed over the folly of the HS2 “bat tunnel”, designed to protect flying bats from passing trains at a cost of £168 million. At Hinkley Point, £700 million is being spent at a new nuclear power station on measures expected to save 0.083 salmon and 0.028 sea trout per year.

These examples of blocked projects and expensive mitigations feed a simple argument: that environmental rules have become overzealous, bureaucratic, and an obstacle to economic growth. In the United States, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson make this case in Abundance (2025), where they argue that the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and related regulations now slow down or block infrastructure, housing, renewable energy, and clean-tech deployment. Reviews take too long, decisions are too litigious, small groups can hold projects hostage, and timelines are unpredictable.

For those steeped in the nature positive movement, this can feel jarring. We are facing not only a climate crisis but a freshwater crisis, a biodiversity crisis, a deforestation crisis, and a pollution crisis. Our destruction of the natural world has become so extreme that we have now transgressed seven of the nine planetary boundaries, a scientific framework developed by Johan Rockström and colleagues to map the safe operating limits of the Earth system. All these breaches (and not just climate change) mean we are massively increasing the risk of generating large-scale abrupt or irreversible environmental changes that threaten the stability of life on earth.

Despite this, it is the economic growth crisis that is top of mind for most citizens and politicians. In countries like the UK, real average wages have barely risen in 15 years, and governments face high debt, and rising demand for public services. Growth is a national necessity. And so the danger for the nature positive movement is clear: if the public starts to believe that nature protection means declining prosperity, then the coalition for a nature-positive future dissolves.

But there’s another way to look at this moment. The work we need to do to halt nature loss, mitigate nature risks, and restore ecosystems isn’t a brake on progress. It can be a new engine of growth.

Why? Because the nature positive transition requires us to create new markets, develop new technologies, and grow the businesses that will deploy them. Water security is a good example. Droughts, population growth, and failing infrastructure will drive demand for smart irrigation systems, ultra-efficient desalination, and next generation water treatment technologies. Food and land systems will require breakthroughs in precision agriculture, drought-tolerant seeds, microbial soil enhancements, as well as sustainable fertiliser and pesticide alternatives. We’ll need new approaches to pollution control and material circularity - better filtration, waste-to-value systems, and advanced recycling. High density housing will need to be built at a vast scale, driving demand for low impact materials, next generation water management systems, and biodiversity positive design concepts. And already today, companies need tools for nature risk management and supply chain traceability.

These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re outlined clearly in the Taskforce for Nature Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) 2025 discussion paper on nature-related opportunities, which calls them the next big growth sectors in the global economy. This transition is similar to what happened with solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles in the early 2000s. At the time, those technologies were niche, expensive, and often dismissed. Today, they are trillion-dollar industries.

Europe and the UK should know this story well, because they helped write the first half of it. Europe led the world in early climate action: from the Kyoto Protocol to the EU Emissions Trading System, from offshore wind subsidies to emissions standards for cars, and from net-zero commitments to major public R&D programmes. The UK and Europe played a central role in shaping global climate diplomacy and national-level climate legislation.

But when it came to the economic upside, Europe and the UK largely failed to capture it. China now dominates every major clean-tech value chain: solar PV, batteries, electric vehicles, wind power components, and the processing of critical minerals. Western governments led on the vision, the goals, the rules, and the early subsidies. China led on manufacturing, scale, and industrial policy and captured the jobs and growth that came with it.

We are on track to repeat the same pattern with nature.

Once again, Europe and the UK are leading on the frameworks: the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), adoption of the TNFD, biodiversity net gain requirements, the EU Nature Restoration Law, and Horizon Europe funding for early R&D. This leadership is valuable. But unless it is combined with an industrial strategy that helps companies design, make, and export the technologies of the nature transition, most of the value will be captured somewhere else.

Turning nature positive into a real engine of economic growth will require a shift in how governments think. Faster permitting is essential, especially for low-impact housing, clean energy, and water infrastructure. Nature positive subsidies become key to support scaling and manufacturing in water technology, agricultural innovation, biotechnology, ecological monitoring, and restoration solutions. Winding down harmful subsidies is equally important, such as those for tax breaks for fossil fuels and VAT exemptions for first generation pesticides. And unlocking capital - such as by mandating pension funds to invest in the innovations of tomorrow - will be critical. For context, China is estimated to have invested >$650bn in the clean energy sector in 2024 alone.

It also means a change for the nature movement itself. For decades, environmentalism has focused on preventing harm: stopping pollution, stopping habitat loss, stopping destructive projects. But the next chapter has to be constructive. The movement needs to become the group that says “here’s how,” not just “here’s why not.”

A nature-positive economy isn’t a constraint. It’s a growth strategy, a competitiveness strategy, and a resilience strategy. The countries that move early, reform their systems, back innovation, and scale the next generation of technologies will lead the global economy in the decades ahead. Those that hesitate won't just miss out on economic growth. They'll find themselves dependent on imported technologies, vulnerable to environmental shocks, and locked out of the green economy they helped inspire. And that is why the nature agenda should not be framed as the enemy of growth. It is, in fact, one of the biggest growth opportunities of the 21st century.

In February, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) approved its Business and Biodiversity...

The climate crisis has long been a corporate priority. But the nature agenda, biodiversity, land use, pollution, and water, is now emerging as an...

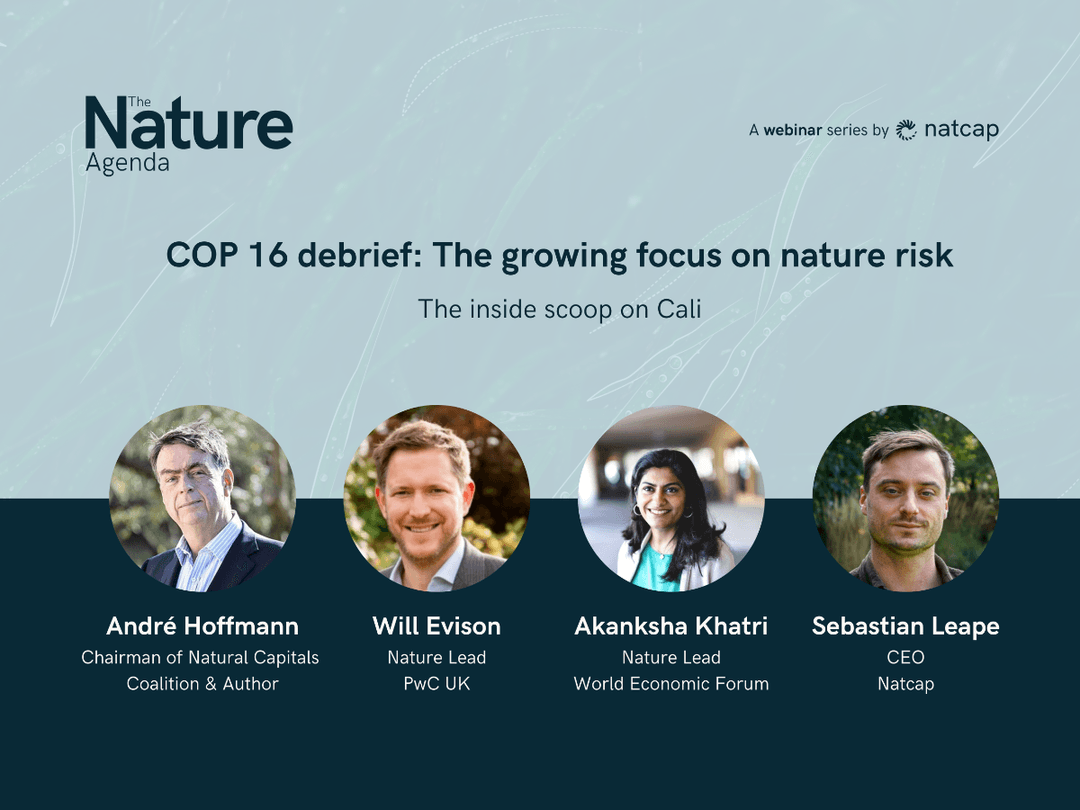

The UN Biodiversity Conference (COP16) in Cali, Colombia, marked a significant shift in how businesses engage with nature and biodiversity. We...